Scleroderma is a chronic condition in which abnormal immune activity drives blood-vessel injury and fibrosis, meaning the body produces too much collagen, leading to thickening and hardening of tissue.

In systemic forms, the disease process can damage small blood vessels and trigger fibrosis in the affected skin and internal organs, which is why scleroderma affects more than appearance alone.

Collagen is a normal structural protein in connective tissue, but in systemic disease it is produced and deposited in excess, contributing to tight skin and scarring in organs such as the lungs and gastrointestinal system.

This organ involvement can include the digestive tract (motility and absorption issues) and the lungs, where fibrosis can affect lung tissue and reduce oxygen transfer.

Because scleroderma can overlap with other autoimmune conditions and present with different patterns of skin and organ involvement, diagnosing scleroderma typically relies on clinical exam plus laboratory testing (autoantibodies) and organ-specific evaluation when internal involvement is suspected.

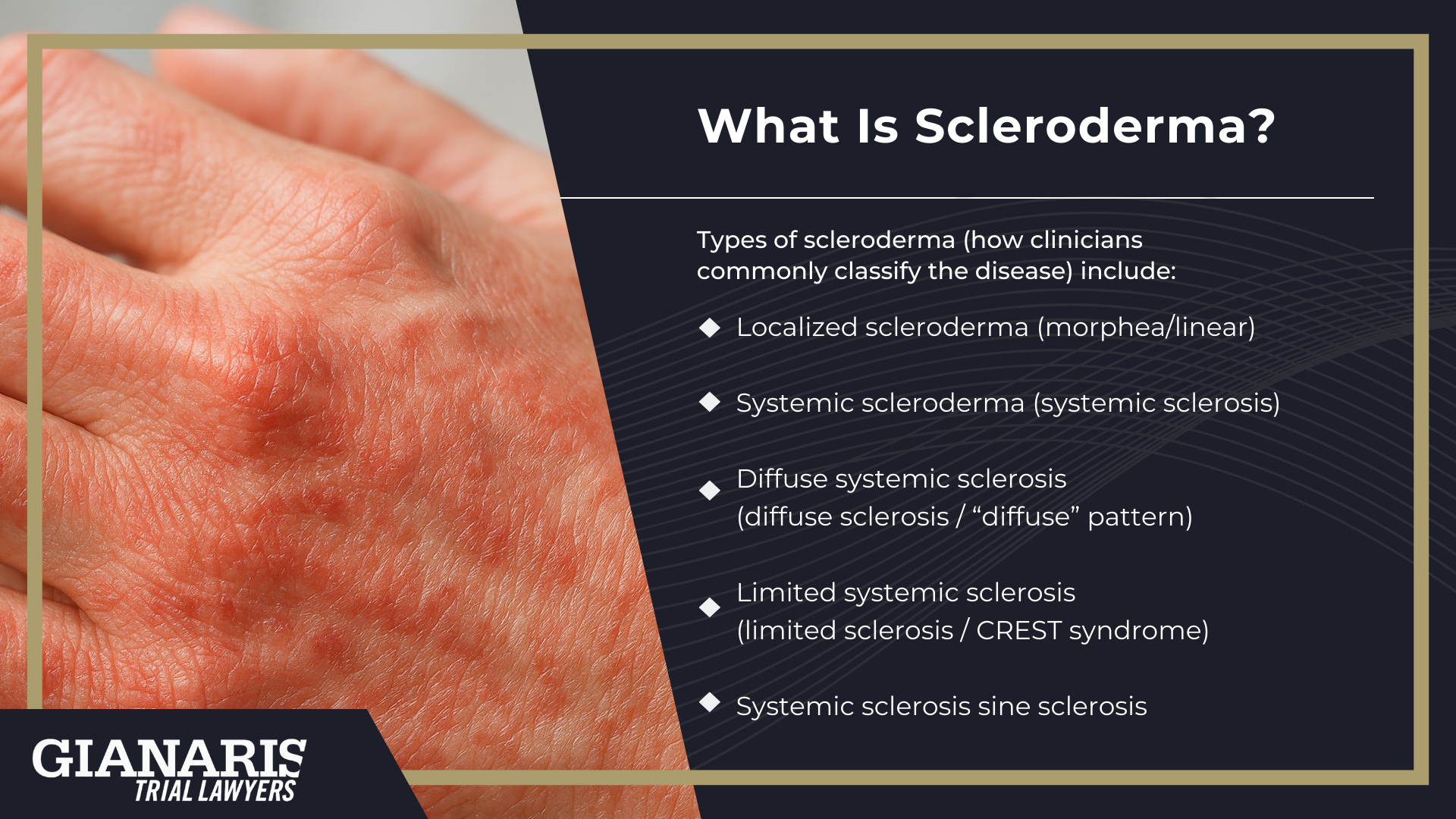

Types of scleroderma (how clinicians commonly classify the disease) include:

- Localized scleroderma (morphea/linear) — primarily affects the skin and underlying tissues without the same pattern of widespread organ involvement seen in systemic disease.

- Systemic scleroderma (systemic sclerosis) — can involve skin, blood vessels, and internal organs, and is commonly divided by the extent of skin involvement.

- Diffuse systemic sclerosis (diffuse sclerosis / “diffuse” pattern) — broader skin involvement and higher likelihood of early internal organ involvement; Cleveland Clinic describes diffuse sclerosis as thickened skin over larger areas and notes it can affect multiple organs at once.

- Limited systemic sclerosis (limited sclerosis / CREST syndrome) — skin involvement is typically more limited in distribution, but internal complications can still occur; “CREST syndrome” is commonly used as a label for this limited form.

- Systemic sclerosis sine sclerosis — systemic disease features without the classic pattern of skin thickening, recognized as a subtype in systemic sclerosis classification.

When building exposure-based cases, the focus is usually on systemic scleroderma, because systemic vascular injury and fibrosis can produce serious multi-organ health issues.

Known scleroderma risk factors include a person’s immune profile and genetics, but reputable medical sources also recognize that environmental factors can play a role in who may develop scleroderma, which is why occupational history matters in certain investigations.

The key is specificity: which exposures occurred, how long they occurred, and whether those exposures align with the occupational risk factors most supported in the medical literature.

Scleroderma Symptoms

Scleroderma symptoms vary widely depending on whether the disease is localized or systemic and which organs are involved at the time scleroderma is diagnosed.

Some people notice early skin or circulation changes, while others first experience internal complications affecting the lungs, heart, or digestive system.

Because the disease can involve blood vessels and connective tissue throughout the body, symptoms may evolve and expand over time rather than appear all at once.

Systemic involvement can create serious risks, including cardiac strain and, in advanced cases, heart failure.

Ongoing care focuses on identifying complications early and helping patients manage symptoms as the disease affects different systems.

Common scleroderma symptoms include:

- Thickened, tight, or shiny skin, often affecting the hands, face, or lower extremities

- Chest pain related to lung or heart involvement

- Circulation problems in the fingers and toes, especially with cold exposure

- Difficulty swallowing due to esophageal involvement

- Digestive issues, including reflux, bloating, and impaired nutrient absorption

- Shortness of breath or reduced exercise tolerance

- Joint stiffness and pain, along with other symptoms tied to connective tissue inflammation

How Scleroderma Can Affect the Body

Once scleroderma is diagnosed, the disease can affect far more than the skin, because blood-vessel injury and fibrosis may involve multiple organ systems.

Damage to small blood vessels can impair circulation and oxygen delivery, increasing strain on the heart and lungs.

When the lungs are affected, scarring or elevated pulmonary pressures can limit breathing capacity and raise the risk of serious complications.

Cardiac involvement may interfere with normal heart function and, in some cases, become life-threatening.

The digestive system is also commonly affected, as fibrosis can disrupt movement of food and absorption of nutrients, contributing to weight loss and fatigue.

Kidney involvement, while less common, can cause sudden or severe blood-pressure changes that require close monitoring.

As organ involvement expands, patients may face a higher risk of hospitalization and long-term disability.

Although scleroderma is not curable, medical management and lifestyle changes can help control complications and improve quality of life by preserving function and reducing symptom burden.

Treatment for Scleroderma

Treatment for scleroderma is individualized and focuses on controlling immune activity, protecting affected organs, and addressing complications as they arise.

Care plans are shaped depending on the type of scleroderma diagnosed, the organs involved, and how active the disease is at the time of evaluation.

A healthcare provider will rely on ongoing monitoring, often including blood tests and imaging tests, to track disease activity and guide treatment decisions.

Because scleroderma can affect multiple systems, management typically involves coordinated care across specialties.

The goal is to slow progression, reduce organ damage, and maintain daily function rather than reverse existing fibrosis.

Common treatment approaches for scleroderma include:

- Medications that suppress or modulate immune activity to reduce inflammation and tissue injury

- Drugs aimed at improving blood flow and protecting small blood vessels

- Targeted therapies for lung, heart, kidney, or gastrointestinal involvement

- Physical and occupational therapy to preserve mobility and hand function

- Ongoing monitoring with laboratory work and imaging to adjust treatment as the disease changes