Pulmonary fibrosis is a form of lung scarring caused by injury to the lung’s interstitium (the tissue around and between the air sacs (alveoli)) that becomes thickened and stiff as scar tissue accumulates.

Mayo Clinic describes pulmonary fibrosis as damage and scarring around/between the alveoli, which reduces normal lung elasticity and gas exchange capacity over time.

Cleveland Clinic likewise characterizes pulmonary fibrosis as scarring and thickening in the lungs and places it within the broader group of interstitial lung diseases.

Pulmonary fibrosis is not one single diagnosis; it describes a scarring pattern that can result from multiple underlying conditions, exposures, or immune processes—so the “why” matters as much as the scarring itself.

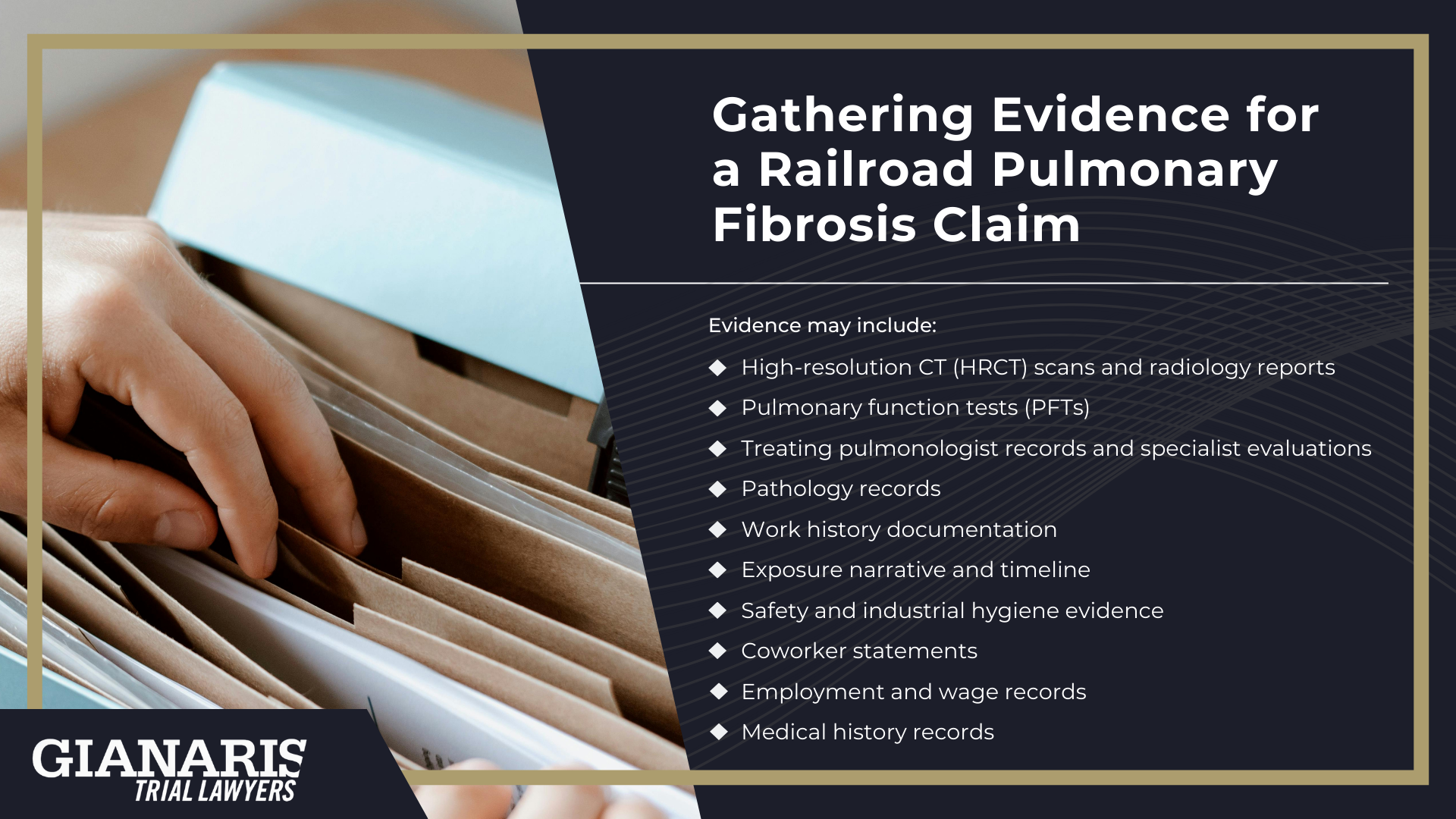

In respiratory medicine, clinicians typically diagnose pulmonary fibrosis through a combination of high-resolution chest CT imaging, pulmonary function testing, and a detailed exposure and medical history, with multidisciplinary review and (in select cases) bronchoscopy or biopsy when the cause remains uncertain.

Types of pulmonary fibrosis (common categories used in respiratory medicine and ILD practice) include:

- Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) — scarring that develops without an identifiable cause; it is one of the best-known fibrotic ILDs and a major focus of ILD research and clinical care.

- Connective tissue disease–associated ILD (CTD-ILD) — fibrosis linked to autoimmune disease involving connective tissue (for example, rheumatoid arthritis–associated ILD).

- Chronic/fibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis — scarring caused by an exaggerated immune response to repeated inhalation of an antigen; chronic forms can resemble IPF on imaging and pathology.

- Occupational pneumoconioses with fibrosis — scarring from inhaled dusts/fibers (e.g., asbestosis, silicosis) that can permanently injure lung tissue and drive diffuse fibrotic change.

- Drug-induced or radiation-associated pulmonary fibrosis — fibrosis that develops after certain medications or chest radiation exposure (classified within ILD etiologies when other causes are excluded).

- Post-inflammatory/post-infectious fibrotic ILD — fibrosis that can follow severe or recurrent lung infections in susceptible individuals, with pattern and timing guiding classification.

- Unclassifiable fibrotic ILD — cases where scarring is present but clinical, imaging, and (when done) pathology findings do not fit a single clear category.

At a high level, pulmonary fibrosis is defined by irreversible structural change: lung damage that becomes fixed scarring—rather than a short-term inflammatory illness.

Some fibrotic ILDs develop a “progressive” phenotype, and clinicians also track destabilizing events such as an acute exacerbation (sudden worsening with new radiographic changes) because that pattern can affect prognosis and evaluation.

Pulmonary fibrosis can also be complicated by pulmonary hypertension, meaning high blood pressure in the lung circulation, which can further affect overall health and is recognized as a potential complication of ILD.

Finally, a growing body of respiratory medicine literature recognizes that pulmonary fibrosis (particularly IPF) can be associated with lung cancer risk, which adds another layer to long-term lung health planning and surveillance.

Symptoms of Pulmonary Fibrosis

Living with pulmonary fibrosis often means adapting to changes that develop gradually as scarring interferes with how the lungs move oxygen through the tiny air sacs.

Early signs may be subtle, but as the disease progresses, breathing becomes more limited and daily activity requires greater effort, which can affect people differently depending on the underlying condition that causes pulmonary fibrosis.

The scarring process is linked to ongoing inflammation and abnormal healing responses, sometimes involving the immune system, which contributes to worsening lung efficiency over time.

As limitations increase, many patients notice a decline in stamina and quality of life, raising understandable concerns about long-term outlook and life expectancy.

While a healthy lifestyle can support overall health, symptoms reflect structural lung changes rather than fitness alone.

Common symptoms of pulmonary fibrosis include:

- Shortness of breath, especially with exertion, as oxygen transfer becomes less efficient

- Dry cough that persists without infection or mucus production

- Fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance as lung capacity declines

- Weight loss or reduced appetite associated with increased breathing effort and systemic effects

- Worsening symptoms over time, placing some individuals at higher risk for complications that further affect daily function

Progression of Pulmonary Fibrosis: Long-Term Health Effects

Pulmonary fibrosis is typically a progressive condition, meaning lung scarring can expand over time and steadily reduce the lungs’ ability to deliver oxygen to the body.

As fibrosis advances, many people require more oxygen to support basic activity, sleep, or exertion, reflecting declining gas exchange capacity.

The pace of progression varies widely.

Some individuals experience a slow, gradual decline, while others worse quickly after a period of relative stability.

This unpredictability is why physicians often monitor patients closely and adjust the clinical course of action based on imaging, pulmonary testing, and functional change.

Certain forms of fibrotic lung disease are more aggressive than others, with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis often cited as the common form associated with faster progression and poorer outcomes compared to some secondary fibrotic conditions.

Over time, increasing scarring can place strain on the heart and pulmonary circulation, raising the risk of complications that extend beyond the lungs.

Acute worsening episodes may also occur, accelerating decline and disrupting previously stable disease patterns.

Understanding long-term progression is essential for planning care, assessing disability, and evaluating how pulmonary fibrosis affects overall health and independence.

How is Pulmonary Fibrosis Treated?

Pulmonary fibrosis does not have a cure, so treatment focuses on slowing disease activity, preserving lung function, and addressing complications as they arise.

The approach depends on the type of fibrosis, how advanced it is, and how quickly it is changing, which is why management is often individualized.

Physicians may use imaging, pulmonary function testing, and sometimes a lung biopsy to clarify diagnosis before deciding on next steps.

In some cases, prior radiation treatments, autoimmune disease, or occupational exposure history influences which therapies are appropriate.

Care is typically coordinated through a multidisciplinary healthcare team, often involving pulmonologists, radiologists, and other specialists.

Treatment planning also accounts for overall health, comorbidities, and functional limitations.

Common treatment options for pulmonary fibrosis include:

- Antifibrotic medications designed to slow the progression of scarring in certain forms of pulmonary fibrosis

- Pulmonary rehabilitation programs that focus on breathing efficiency, endurance, and physical conditioning

- Supplemental oxygen therapy when blood oxygen levels decline

- Vaccinations and infection prevention to reduce respiratory complications

- Evaluation for lung transplantation in advanced or rapidly progressive cases

- Supportive therapies aimed at managing associated conditions and maintaining daily function

Even with treatment, pulmonary fibrosis often requires ongoing monitoring and adjustment of care strategies over time.

Some therapies are intended to stabilize disease rather than reverse existing scarring, which is why early diagnosis can matter.

For individuals with progressive disease, discussions about advanced care planning may become part of the long-term strategy.

Treatment decisions are frequently revisited as imaging, lung function, and symptoms change.

The goal is to balance disease control with quality of life while preparing for future care needs if progression continues.